A Tale of Two Graphs (and More)

An Investigative History of America's Overdose Crisis

Part One: The Narrative of the Four Phases

Looking back over the past three decades, a narrative consensus has emerged that America’s overdose crisis unfolded in four phases. Phase One consisted of increased prescribing of pharmaceutical opioids for pain, initiated by the introduction of OxyContin in early 1996. Phase Two was triggered in 2010 when OxyContin was reformulated to make it more difficult to crush or dissolve, thereby driving its abusers to a resurgent heroin market. Phase Three began around 2013 or so when illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF) crept into the heroin supply, eventually to replace it almost entirely. And Phase Four is what we are seeing now: the proliferation of ever-more-powerful novel compounds concocted in clandestine laboratories and pressed into counterfeit pills, killing naive recreational drug users and experienced addicts alike.

This overarching narrative is a useful but problematic construct. It isn’t false per se, but it obscures key dynamics of the overdose crisis in ways that misdirect efforts to mitigate it. It also has been built to explain more than it can by people who for various reasons are invested in it. The PAIN GAME tells a different story — or rather, the many stories that wash over and around the retrospective Four-Phase Narrative.

In 2004, when we began filming The PAIN GAME, we adopted an open-ended (and open-minded) approach to what was then called the opioid crisis, immersing ourselves in all of its complexities and contradictions. Some may find the investigative history we have produced inconvenient because it undermines the structural integrity of the Narrative of the Four Phases. Like flood waters, history flows where it will and finds its true channels.

Some may find the investigative history we have produced inconvenient because it undermines the structural integrity of the Narrative of the Four Phases.

The central assertion in Phase One of the standard narrative of the overdose crisis is that rising opioid prescribing for chronic, non-cancer pain created an epidemic of opioid use disorder among patients that resulted in rising overdose death rates.

There is a correlation, and it looks like this:

What we see in this ubiquitous graph (published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with data from the Drug Enforcement Administration) is a nearly four-fold increase in pharmaceutical opioid sales between 1999 and 2011 coincident with a roughly four-fold increase in prescription opioid deaths. This visual triggers the deeply ingrained assumption in the public mind that the opioids were coming from “pill mills” — shady clinics where a motley assortment of fake pain patients would shuffle through, and after perfunctory examinations, receive fraudulent prescriptions for narcotics. It is taken as axiomatic that the prescribers in these clinics were corruptly influenced by the strong-armed marketing tactics of opioid manufacturers, most notoriously Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin.

There is some truth to this impression. Pill mills did exist; but for reasons that The PAIN GAME explores in detail, the distinction between legal and illegal opioid prescribing was never as clear as it should have been. Indeed, the key to understanding how pharmaceutical opioids contributed to the overdose crisis lies not in the proliferation of purported pill mills, but in the expansion of good-faith, legal prescribing, and the medical, regulatory, and commercial environment in which it took place.

The key to understanding how pharmaceutical opioids contributed to the overdose crisis lies not in the proliferation of purported pill mills, but in the expansion of good-faith, legal prescribing, and the medical, regulatory, and commercial environment in which it took place.

When we go back and look at what was really happening in the mid-1990s, we see that the pain movement long pre-dated the introduction of OxyContin. It was begun by kind-hearted medical professionals who had been carefully incorporating opioid medications into the palliative care of cancer and AIDS patients throughout the 1980s with gratifying results.

It has been known empirically for thousands of years that opioids are effective in alleviating pain, as well as potentially addictive. But for the past century, doctors had been wary of prescribing opioids for chronic pain because they believed that with repeated exposure any analgesic effect the medications might convey would be overwhelmed by the risk of addiction that rode along with it. Starting in the 1960s, however, researchers had begun to parse opioids’ mechanisms of action and revisit their pain-treating potential. They found that the human nervous system contains opiate receptors and peptides that have evolved to fit them so well that they perfectly mimic the effects of exogenous opioids.[1] Scientists dubbed these peptides endorphins, an elision of "endogenous" and "morphine."[2]

In healthy subjects, pain is controlled by a homeostatic system in which endorphins — stimulated by exercise and other factors — cushion the effects of noxious stimuli. Studies clearly indicate, however, that with severe injury or chronic illness this system can be worn down or disrupted. Acute pain that is not treated with exogenous opioids can develop into chronic pain, and untreated chronic pain can become a malignant, progressive disease in itself.[3]

In light of this discovery, it made perfect sense mechanistically to propose that the administration of pharmaceutical opioids in a timely fashion — and only in rare cases for an indefinite duration — would prevent the development or worsening of chronic pain. Thus the imperative to treat pain expanded beyond that of relieving a patient's suffering — although this remains an important consideration — to protecting the patient from the health risks of pain itself. And it followed that the pain leaders felt compelled to extend their treatment protocol beyond terminal care to patients living with any number of painful conditions.

The imperative to treat pain expanded beyond that of relieving a patient's suffering — although this remains an important consideration — to protecting the patient from the health risks of pain itself.

So what went wrong? It is clear in our account that the pain leaders were not naive about opioid medications’ inherent risk of addiction. The best among them worried about it quite a bit, and they worked with their counterparts in academic addiction medicine to identify addiction risk factors in pain patients. Still, they were naive to think that their carefully crafted, multi-modal pain treatment model could be disseminated intact throughout the U.S. healthcare system without contributing to an addiction crisis that was already underway. The collaborative model they had developed required commitment, expertise, constant vigilance, and the time and attention of pain psychologists, pharmacologists, physical therapists, and other adjunct professionals. Opioids were just one of their protocol’s components, often the cheapest one — and this was a problem.

The U.S. emerged from World War II with a unique system of providing healthcare insurance primarily through employers. Over the coming decades, the insurance industry would steadily become more profit driven, until, by the mid-1990s, it was clear that private insurers were acting as gatekeepers for the entire healthcare system; and they were rationing care with the federal government’s blessing. Health insurers' ethical stance shifted from promoting the well-being of their subscribers to maximizing the gains of their shareholders and minimizing the costs to Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal programs (most of which they administer).

As detailed by pain psychologist Michael Schatman, Ph.D.,[4] who has studied this ethical shift closely, chronic pain care was one of its biggest casualties.[5] Although interdisciplinary pain programs are cost effective as well as clinically effective in the long run, insurance companies have treated them with a short-sighted approach by carving out some of their less expensive components for reimbursement and denying coverage for the rest. In 1999, there were 1000 collaborative pain programs in the U.S., but by 2015, they had dwindled to fewer than 100 (outside the Veterans Administration)[6] — a telling downward line to add to our graph, perhaps. At the end of the day, chronic pain patients were often left with just a 15-minute office visit with a primary care provider and a prescription for opioids (if they were lucky).

In a classic twist that further illustrates how crassly commercial our healthcare system has become, some of the companies that make those opioid medications would then go on to market them outside of the context of the interdisciplinary pain care model and into nooks and crannies of medical practice where they didn’t belong. That rising green line of Opioid Sales in the CDC graph above represents opioid prescribing that was intended to meet a real need, but that doesn't mean the medications were actually reaching the appropriate patients.

That rising green line of Opioid Sales in the CDC graph above represents opioid prescribing that was intended to meet a real need, but that doesn't mean the medications were actually reaching the appropriate patients.

Now take a look at the blue line labeled Rx [Prescription] Opioid Deaths in that graph and hold it in your mind. Most fatal overdoses are what medical examiners call multi-drug intoxications, where the decedent has taken a lethal combination of drugs, prescribed or otherwise. It is often impossible for them to determine which substance to blame in such cases, so they guess. As a statistic, the designation is vague anyway. The data that are reported to the CDC and aggregated into graphics representing fatal opioid overdoses are deaths that have been ruled as opioid involved. This really just means that these are cases in which an opioid was in the mix, not that any given opioid was the definitive cause of death.

This vagueness becomes perilous when there is a criminal investigation or civil lawsuit looming in the background. In the course of reporting on the prosecution of physicians for (alleged) illegal prescribing, healthcare fraud, and wrongful deaths, we have examined the autopsy reports and clinical records for scores of deceased patients whose deaths were ruled as accidental overdoses. We have seen how the presence of such legal action pushes medical examiners toward putting a prescribed drug at the top of the list in multi-drug intoxications.

But it gets worse than that. We’ve also seen intense pressure to rule deaths as prescription drug overdoses even when it is not clear that the patient died of an overdose at all. In many of the coroner’s reports we have seen, a number of potentially fatal health factors or events were noted as present at the time of death: heart attacks, seizures, late-stage autoimmune disease, kidney failure, advanced diabetes, severe infections, morbid obesity, and so on. And yet, because these fragile pain patients were being treated with opioids, almost all of their deaths were ruled as accidental overdoses. In Dr. Fisher's case (the first in the series we covered for The PAIN GAME), one of his patients was decapitated in a car accident, and her death was ruled an overdose (and pinned on him). Not only was the level of oxycodone measured in her blood at autopsy consistent with her treatment, she was the passenger in the vehicle.

It is important to keep all this in mind when we ponder that rising blue line of Rx Opioid Deaths in the CDC graph above. It is not as firm as it looks. For a long time, the CDC, the DEA, federal prosecutors, plaintiffs’ attorneys, and compliant reporters have fed the public a simplistic mantra regarding fatal prescription opioid overdoses: that every patient who was prescribed an opioid for any reason was put in immediate danger of a lethal addiction; and conversely, that just about every data point on that rising blue line of Rx Opioid Deaths represents an unsuspecting, opioid-naive patient dutifully following her doctor’s orders. This is a deeply cynical conceit: it is incurious about the lived experiences of those who have perished, and thus it offers no protection to others whose lives may be in danger.

Because these fragile pain patients were being treated with opioids, almost all of their deaths were ruled as accidental overdoses.

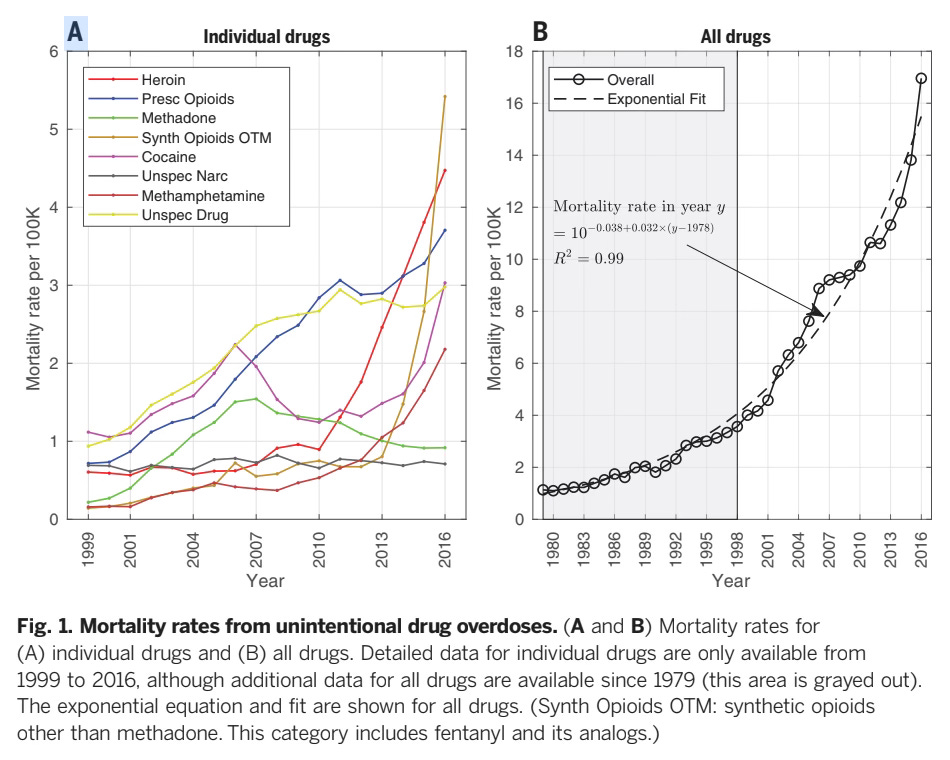

In 2018, a team of researchers led by Donald Burke, M.D., and Hawre Jalal, M.D., Ph.D., at the University of Pittsburgh published a powerful study in the journal Science tracking fatal drug overdose trends in the U.S. from 1979 through 2016.[7] While acknowledging the problems with the way overdose deaths are reported, they gathered a large data set of aggregated deaths from all drugs of abuse and plotted them on a curve. The result is unmistakable: in the nearly four-decade time frame they studied, the incidence of fatal drug overdose rose at a remarkably smooth and exponential rate.

This is their diptych graph:

Here, the blue line of Prescription Opioid Deaths in the panel on the left rises along with lines tracing deaths from heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and other illicit substances. And that bubbly aggregated line in the panel on the right clearly shows that America has a drug problem, with or without the pain movement.

Using fatal overdose as an (albeit imperfect) indicator of drug use, the authors of the study propose that in analyzing which drugs are popular in particular places at particular times, it is important to consider what they call “push” factors, such as supply chains, illicit manufacturing technologies, and black-market prices. But in pondering the dramatic upward sweep of the trend overall, it is evident that there must be “pull” factors underlying it. In other words, there must be sociological and psychological reasons why so many Americans seek out drugs to their peril.

America has a drug problem, with or without the pain movement.

Looking closely at the two panels of the Jalal graph, we can pick out the inflection points that mark each of the Four Phases. Deaths involving prescription opioids contribute to the aggregated line as it rises through the 1990s in the panel on the right. In the panel on the left, the red line of heroin mortality kinks up sharply precisely in the year 2010. And in 2013, the orange line labeled synthetic opioids other than methadone, which denotes deaths attributed to IMF and other novel compounds, begins to skyrocket.

Although these trends seem obvious as plotted here, we would be foolish to assume that their composition is anything but complex. Not only are both push and pull factors constantly at work, they often act synergistically — as push-me/pull-you factors, if you will. (Or pushmi-pullyu, as the term originally appeared in Hugh Lofting’s The Story of Dr. Dolittle.) You wouldn't learn that from the Narrative of the Four Phases, however. In countless instances, the Narrative’s purveyors have made some simplistic assertion or other regarding opioids by trotting out one end of a pushmi-pullyu while studiously ignoring the other end prancing along backwards behind it.

Part Two: The Arrival of Three Waves

In November of 2004, our Director, Erica Modugno Dagher, attended the annual meeting of the National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators (NADDI) in Nashville to film presentations and interview key figures. This is where she met Commander Burke, shown above for the second time. I have repeated his clip here to add the second sentence. He says he’s learned one thing in law enforcement, but he states two things.

Like the pushmi-pullyu, these two things are joined in synergy and opposition. When a story is presented as a simplistic, two-sided, zero-sum, good-vs.-evil melodrama, we should suspect that commentators are reaching beyond what they actually know. Such a framework pushes reporters away from sources with direct (and messy) experience of an issue and pulls them toward officials, academics, and other figures who have positioned themselves as experts when their knowledge is partial, tangential, or self-serving. Commander Burke evidently has learned this from his long experience working as a police officer in Cincinnati, rising through the ranks to manage teams investigating ever-more-elaborate, drug-related crimes.

When a story is presented as a simplistic, two-sided, zero-sum, good-vs.-evil melodrama, we should suspect that commentators are reaching beyond what they actually know.

Established in 1989, NADDI is a non-profit that helps federal, state, and local law enforcement officers collaborate with medical board officials, private security professionals, and various regulators to combat pharmaceutical drug diversion. Diversion is an important storyline in The PAIN GAME. It occupies much of the space between the green and blue lines of the CDC graph shown the Part One of this article.

If the deaths that occurred in Phase One of the overdose crisis had been primarily among pain patients overdosing on their own medication (and nothing else), it would have been purely a healthcare issue, a medical misadventure that probably would have self corrected pretty quickly. It is the diversion of that medication into the wrong hands that de-legitimizes it and brings law enforcement into the picture. When an opioid pill leaves the closed system in which it is manufactured, delivered by a wholesaler to a pharmacy, and dispensed to a patient with a valid prescription, it becomes as illegal as a baggie of heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine.

At the time Erica interviewed him, Commander Burke was in charge of the Warren-Clinton Drug Task Force in Southwest Ohio. He was also the coordinator of pharmaceutical drug diversion for the Southern Ohio High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area initiative, which he had established in 1990 as one of the first HIDTAs in the country. When Congress established the Office of National Drug Control Policy with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, it gave the Director of that office, in consultation with others, the authority to designate certain problematic areas within the U.S. as HIDTAs. Such a designation brings federal funding to the area and allows federal law enforcement agencies to partner with state and local officers in special task forces.[8] Because of its Rust Belt demographics as well as its location at the intersection of major transportation routes, Southern Ohio was known to be a nexus for illicit drug traffic. The growing black market for pills would largely run through this same infrastructure.

It is clear from the presentations given at the 2004 NADDI conference that the illicit and licit markets for drugs are not as black and white as they should be. Together they comprise one big ecosystem, with a flimsy barrier dividing them. Combatting pharmaceutical drug diversion is a less dangerous beat than going after drug running by gun-toting cartels, of course. Policing it requires a certain finesse, however, since the “drugs” originate as legal, regulated products and are diverted from the healthcare system in countless ways, often by regular people.

For this reason, Commander Burke and his NADDI colleagues had learned how to work with stakeholders outside the traditional law enforcement world, such as healthcare providers and pharmaceutical industry professionals. Much like the pain leaders struggling to blaze a new trail through the healthcare system, NADDI's leadership was trying to do something innovative within law enforcement. They used their annual conference to educate street cops, highway patrol officers, sheriffs, and the like about the nuances of prescription drug abuse and diversion. Their 2004 conference was their biggest one to date, with just over 300 attendees.

Much like the pain leaders struggling to blaze a new trail through the healthcare system, NADDI's leadership was trying to do something innovative within law enforcement.

One of the most impressive presentations Erica filmed at the NADDI conference was given by a registered nurse and poison information specialist from Maine named Coleen Muse, who spoke about methadone maintenance. Perhaps because she was following a physician from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) who had just given a garbled talk marred by sweeping assumptions and mish-mashed data, Ms. Muse starts right out by saying that she will speak only about what she has learned first hand while working with addiction patients in Maine. She came from law enforcement, she says, and it was an eye-opening experience to work in a methadone clinic. She had to unlearn the unsavory image of the typical addict she had picked up from rumor and TV shows and accept the arriving patients as they were.

Ms. Muse then proceeds to give a straightforward and compassionate description of methadone maintenance as a form of harm reduction. Most interestingly, she describes the people who presented at the clinic and what had brought them in. During the five years she worked there, she saw three overlapping waves of patients. Wave One was people in their mid-30s to late-40s who had begun injecting heroin in their youth and now were motivated to quit because of mounting health, financial, or legal problems.

Then came Wave Two, the abandoned pain patients. These were middle-aged to older adults who had been receiving appropriate opioid therapy from their primary care physicians. Then they had gotten cut off when they needed increasing doses, and their doctors got spooked. Ms. Muse calls them the forgotten patients. "They may not be actually abusing [the medication]," she says. "It comes back to that abusing/mis-use thing, and we've got to decide what to call what."[9] Rather than go out on the street to buy pills, these patients would show up at the methadone clinic, where they were kindly taken in and treated for pain with liquid methadone as if they were addicts. It was better than nothing. (Opioid use disorder is often treated with methadone in liquid form dispensed at specialized clinics. Chronic pain can be treated with methadone in pill form, prescribed at doctors' offices and filled at regular pharmacies.)

Wave Three was the most frightening, Ms. Muse says. During the last two years she practiced at the clinic, she began to see young adults who had begun using opioids as teenagers, taking pills like Vicodin and Percocet. They had not been prescribed these medications but were popping them recreationally at parties, and then buying them on the street or stealing them from friends and family members. As their tolerance built, they would start crushing and snorting the pills, and in some cases would even learn how to liquify and inject them. By the time these patients showed up at the clinic, they had full-blown opioid use disorder; but they also had jobs, Ms. Muse explains, or even young children. They couldn't afford to be sick for weeks at a time to go through opioid withdrawal, so it looked like they were going to have to be maintained on methadone indefinitely.

The most problematic patients with opioid use disorder were young people who were getting pills straight from an abundant black market.

Coleen Muse gave this presentation in 2004. She was talking about a timeframe of about 1997 to 2002. Her honest assessment of the state of opioid use disorder in Maine during that period is invaluable information. From it we learn that, at least in Maine: 1) intravenous heroin use had been persistent for decades when the pain movement began; 2) many pain patients who were compliant with their treatment — and doing well — were being abandoned by their doctors; and 3) the most problematic patients with opioid use disorder were young people who were getting pills straight from an abundant black market. Our reporting is full of historical snapshots like this. It is instructive to map them onto the Narrative of the Four Phases to see what they illustrate.

The oldest of the patients in Ms. Muse's Wave One would likely have been Baby Boomers who began using heroin in the 1960s and '70s when they were in their teens or early twenties, the age at which people are most vulnerable to developing a substance use disorder. Some may have become addicted while serving in the Vietnam War; others while protesting it as part of an emerging counterculture. And others were coping with poverty and racial discrimination in grim, inner-city neighborhoods, impatient for the nascent Civil Rights Movement to improve their lives.

Heroin use persisted through the cocaine boom of the 1980s (they were often used together), while its purity steadily rose from between 3% and 10% in the 1970s and '80s to a whopping 40% in 1994. In 1991, Colombian cartels had started ramping up heroin production to compensate for declining demand for cocaine, and they were aggressively pushing it through their existing distribution networks in the U.S.[10] Fatal heroin overdoses rose steadily during this time, as we can see in the Jalal graph in Part One of this article. This is the backdrop against which OxyContin made its debut in 1996.

It is difficult to study illicit drug use. Researchers must blend data sets from treatment centers, law enforcement, emergency departments, and so on — all of which have acknowledged limitations. But with hard work and discernment, veterans of the field such as Theodore J. Cicero, Ph.D.,[11] have managed to elicit some clear trends over time.

As the availability of heroin spread from major cities and into suburban and rural areas, its use became entangled in a yin-yang dynamic with the abuse of prescription opioids by injection or inhalation. Dr. Cicero and his colleagues found that users were switching back and forth between the two depending on which was cheaper or easier to obtain at any given place or time. In the 1990s, the number of heroin-dependent people who reported initiating their habit with pills overtook those who had started with heroin itself.[12] This trend would begin to reverse in 2010 at the beginning of Phase Two of the overdose crisis, with heroin initiation rising again. By 2015 or so, heroin would overtake pills and resume its position as the opioid of first abuse among a sample of people presenting to treatment centers with opioid use disorder.[13]

It is notable that of the many pain patients we have interviewed over the years who were having difficulty getting medication, few of them said they would switch to heroin if they had to. Pain patients take their medications orally (or by transdermal patch or intrathecal pump). Like most people, they regard intravenous drug use as belonging to a sinister netherworld they would never want to venture into. They might go to the black market to buy pills, but only with great reluctance.

This is a patient named Darlene Oakes (now deceased), whom Erica interviewed in 2005.

Darlene eventually was able to get good care from Dr. Frank Fisher. After his arrest she continued her treatment with Dr. Forest Tennant. (We will see more of Darlene in future articles and hear her narrate her harrowing medical story.) If Darlene hadn't found Drs. Fisher and Tennant (and if she had lived in Maine), she might very well have been one of the forgotten patients in Ms. Muse's Wave Two.

You start doing it to be cool, and then it becomes an escape from your mounting problems.

During a break in the NADDI conference, Erica grabs her camera and wanders into the hotel gift shop, where she finds a young woman alone behind the cash register. She boldly asks the cashier if she has ever had a problem with prescription drugs. With admirable poise and candor, the young woman — I'll call her Laura — replies: "I've tried prescription drugs. I've done 'em illegally. I've been hooked on 'em. I've gotten off of 'em."[14]

She started when she was eleven years old, experimenting with marijuana and cocaine and then moving on to Demerol, Valium, OxyContin, and other prescription medications that older kids were stealing from their parents' medicine cabinets. It is common, she says, you start doing it to be cool, and then it becomes an escape from your mounting problems. Laura belongs precisely to the cohort of Ms. Muse's Wave Three. She was lucky because her parents were able to get her help when she finally overdosed (on acid). Now, at the age of 20, she tells Erica proudly that she has been clean for four years.

Notice that there's a pushmi-pullyu embedded in this account. When Laura says that kids she knew were stealing pills from their parents, she is actually telling us two things. She is confirming what Ms. Muse said about young people taking pills from friends and family. The other thing to note is the fact that the pills were sitting there in medicine cabinets to be taken in the first place. That is, the people for whom they had been prescribed had evidently forgotten about them — or were taking them in a measured manner — which indicates that they did not find them addicting.

So, where in this picture do we find the patient who receives a valid prescription for pain and goes on to develop opioid use disorder? Is it the high school student who is prescribed 30 Percocet pills following a wisdom tooth extraction when five pills would have been enough? Is it the star college athlete who takes one for the team and then is patched up and drugged up so he can go back into the big game? Is it the surgical patient whose surgeon doesn't want to hear about it when her pain persists longer than the expected healing time? Is it the car accident victim who is discharged from the hospital with a bottle of oxycodone and is lost to follow-up the moment he walks out the door? Is it the gunshot victim whose pain is amplified by the trauma he has experienced, and he cannot get mental health care? Is it the well-dressed, middle-aged lady with fibromyalgia who neglects to tell her family doctor she has a drinking problem — and her doctor never thinks to ask? Or is it the poor person with a painful illness whose life is rendered so precarious by food, housing, and transportation insecurity that she cannot obtain regular meals, let alone make it to scheduled appointments or adhere to a complicated pill regimen? It's likely all of the above, but here's the thing: no one really knows. And anyone who says he knows is reaching.

We do know a bit about chronic, non-cancer pain patients who receive consistent, long-term opioid therapy from physicians well trained in the art and science of pain management (and who have no history of addiction). A Cochrane meta-review published in 2018 confirmed what the pain community had been saying all along: their risk of developing opioid use disorder is less than one percent.[15] But these are the Darlenes, the lucky ones. They comprise a tiny subset of the patients who were strewn across the pain landscape in Phase One of the overdose crisis.

Part Three: A Hierarchy of Scams

Why would a doctor abandon a legitimate, compliant chronic pain patient doing well on her medication, like Darlene? This thorny question brings us to the heart of the action in The PAIN GAME.

Many doctors practicing in communities far from the pain leaders' academic medical centers welcomed the call to treat chronic pain more aggressively because they were frustrated that, for so long, they had had so little to offer patients like Darlene. They wanted to believe that opioids could be prescribed safely because the alternatives — such as NSAIDs, steroids, or surgery — can be quite damaging. At the same time, however, they were seeing the signs of rising illicit drug use in the general population, and they were already feeling the pressure from the black market for pills. They were constantly having to fend off patients who would fake or exaggerate pain — or lie about past drug use — to try to scam a prescription out of them.

Who were these scammers? Some were dealers, or people manipulated by dealers. Some were people with opioid use disorder who couldn't get treatment — only about 5% could in the early years of the overdose crisis — or they didn't want to be treated. Some were users of cocaine or methamphetamine, and they would sell their prescribed opioids so they could buy their drug of choice. Some were just people who needed money. Others were legitimate pain patients who needed medication but could not afford to fill a prescription without selling part of it. And then there were the patients in severe pain who needed high doses. Even Darlene was scamming at one time, because she could not get enough medication without stringing along three doctors at a time.

If doctors had been handing out opioids "like candy," as many accounts would have us believe, then we would not have seen so many people trying to scam them. We learn from Commander Burke and other speakers at the NADDI conference that real pill mills — where one could explicitly buy a prescription from a doctor — were rare, and they usually could be shut down pretty efficiently by state regulators. Most of the pills that made their way from doctors' offices to the streets in Phase One of the overdose crisis were prescribed legally by well-meaning doctors to desperate or dishonest patients.

Most of the pills that made their way from doctors' offices to the streets in Phase One of the overdose crisis were prescribed legally by well-meaning doctors to desperate or dishonest patients.

Getting scammed should not make one a criminal, obviously, but few members of law enforcement were willing to follow NADDI’s approach and work with doctors to understand the difference between legal and illegal prescribing. Law enforcement officers are habitually suspicious almost by necessity, seeing everyone as a potential bad guy to be apprehended (although prosecutors, in theory, are supposed to be more discerning). Medical professionals, on the other hand, are trained to be accepting of their patients. They view their patients’ problematic traits or behaviors as signs and symptoms that should be noted and addressed as part of a treatment plan. The pain movement put the two groups on a collision course.

When investigating pharmaceutical drug diversion, the DEA especially tended to fall back on the tactics of traditional drug prosecutions by apprehending scammers selling pills on the street, turning them into snitches, and working their way up the chain of flipped witnesses to the hapless prescriber at the top. The very format of such a prosecution makes that doctor look like a kingpin, makes her practice look like a pill mill, makes her patients look like addicts — and makes the agents, investigators, and prosecutors who pull it off look like they caught a big fish.

Over our many years of reporting for The PAIN GAME, we have watched (and filmed) this continual struggle between the pain community and law enforcement harden into a bitter standoff. Physicians saw colleagues they knew to be of good character harassed, investigated, and sent to prison for prescribing opioids and other controlled substances appropriately. With each high-profile conviction of a pain-treating doctor, more of the remaining prescribers would realize that practicing pain management responsibly would not protect them from law enforcement. All it took was for a few of their prescriptions to find their way to the street and they could find themselves in the crosshairs. The risk wasn't worth it, so they would switch to another area of practice. Thus, even during Phase One, while prescription opioid sales were still rising, it became increasingly difficult for legitimate chronic pain patients to obtain consistent long-term opioid therapy.

Physicians saw colleagues they knew to be of good character harassed, investigated, and sent to prison for prescribing opioids and other controlled substances appropriately.

It has often been said that drug policy is plagued by unintended consequences. In covering case after case of doctors wrongly convicted under the Controlled Substances Act, we would come to question this truism. The enforcement of drug prohibition and control has certainly produced collateral effects that may have been unforeseen by policymakers. As we pursued our reporting, however, it became untenable for us to believe that these effects were entirely unwelcome. On the contrary, they were embraced and perpetuated by vested interests.

Health insurance companies save money when high prescribers are shut down and their patients scattered to the winds, especially if those patients have costly chronic illnesses. The federal government saves money if they are on Medicare. States save money if they are on Medicaid or Workers’ Compensation. Prosecutors are rewarded when they win high-profile cases against medical professionals in which the defendants serve long sentences mandated by drug laws. Lurid media coverage of such cases gives the DEA leverage to press Congress for ever-increasing budgets. Cars, houses, and medical practices are liquidated in civil asset forfeiture to fill the coffers of law enforcement at every level. Plaintiff’s attorneys earn fat fees from wrongful death settlements when they can persuade the family members of (alleged) fatal overdose victims to twist the truth a bit and blame the doctors who were trying to help their loved ones. Such nefarious activity has contributed mightily to the overdose crisis, but it has been obscured by the Narrative of the Four Phases.

The biggest problem with the Narrative of the Four Phases is that it can be told in a way that asserts a dubious postulate about opioid prescribing for pain, and then tries to demonstrate that the events occurring after a prescription is written are logically determined by it. In other words, in its most reductive form, the Four-Phase Narrative adopts the structure of a mathematical proposition to contain the history of the overdose crisis within a closed, internally consistent theorem that cannot be challenged. Its initial postulate relies upon an unforgiving version of the "magic molecule" theory of addiction described in our earlier article, Moving On: that mere exposure to an opioid exposes a person to an overwhelming risk of addiction, because the opioid molecule is so potent it maintains a grip on its victim's brain forever. If this reductive theorem should succeed in explaining all of the sequential phenomena of the overdose crisis, then it would establish as a foundational truth the idea that the bulk of opioid overdose deaths we’ve seen over the past few decades can be ascribed to opioid prescribing for pain.

The biggest problem with the Narrative of the Four Phases is that it can be told in a way that asserts a dubious postulate about opioid prescribing for pain, and then tries to demonstrate that the events occurring after a prescription is written are logically determined by it.

Let's go back to the CDC graph we presented in Part One of this article and walk through the steps of the theorem. First we posit that the rising blue line of Rx Opioid Deaths describes the tragic fate of thousands of acute or chronic pain patients who were treated with an opioid, and that they became addicted and died as a direct result of that treatment. From this it follows that by the end of Phase One, we can assume that an enormous percentage of those pain patients who are still alive are struggling with opioid use disorder, and that they are abusing their medication. Next, in 2010, when OxyContin is refitted with an abuse-deterrent coating, these patients are compelled by the grip of their addiction to switch to heroin, thereby driving up heroin deaths. In the third step of our theorem, when heroin is displaced by more-deadly IMF and its nasty chemical relatives in Phase Three, it is inevitable that even more of these erstwhile pain patients will succumb to fatal overdose. We’ll get to Phase Four in a bit.

Notice that this entire proposition hinges on the reformulation of OxyContin at the juncture of Phase One and Phase Two. Here we are confronted with two problematic corollaries: 1) that the pain patients in Phase One had become addicted specifically to OxyContin in meaningful numbers; and 2) that they were injecting or snorting it. They would not have been affected by OxyContin's reformulation if they had been taking a different opioid, obviously. If they had been prescribed OxyContin but were taking it orally, then there is no way we can assume that many of them were misusing it. As Ms. Muse pointed out in her presentation at the 2004 NADDI conference, there was no consensus at that time — or even now, really — on how prescribers should recognize misuse (or signs of addiction) among pain patients taking their medication orally. (This is a major issue throughout the history of the pain movement, having to do with so-called red flags. We will have much more to say about this in future articles.)

Despite an explosion in sensational news reporting in the early 2000s about its abuse, OxyContin’s adoption in both the licit and illicit markets was always limited by its price. It was a patented medication competing with an array of generic opioid medications, most of which had no abuse-deterrent properties at all. In fact, OxyContin's active ingredient, oxycodone, was itself widely available at the time in naked, unalloyed, smashable, dissolvable pills.

Among addiction patients Dr. Cicero and his colleagues surveyed from late 2010 to late 2013 who were switching to (or switching back to) heroin from prescription opioids, 31.7% said that ease of inhalation or extraction was a factor. This indicates that a sizable minority of them were indeed tampering with coated pills, most likely OxyContin. But at the same time, 94% of this overall group of patients also cited cost (relative to heroin) as the determinant in their switch.[16] This points us in a different direction.

While the old OxyContin was indeed attractive because it packed high dosages, its abusers still had other pharmaceutical options — until the black market for opioid pills contracted as a whole. If the cost of pills was rising after 2010, as Dr. Cicero's subjects reported, the law of supply and demand would indicate that the overall supply was going down; and in fact, the survey participants said that all prescription opioids had become more difficult to obtain. With this in mind, the reformulation of OxyContin recedes in importance in the transition from Phase One to Phase Two. We need to look for factors that would be depressing opioid prescribing across the board, and driving prescription opioid abusers to the heroin market.

Also, it was never as clear as we've been led to believe that during Phase One it was OxyContin that was the main driver of rising prescription opioid abuse, or that its abusers were predominantly current or former pain patients. One study found that among 27,816 subjects admitted to 157 addiction treatment programs in the United States from 2001 to 2004, only 5% reported prior use of OxyContin, and 78% of them said they were never prescribed the drug.[17] This is consistent with data from SAMSHA's National Survey on Drug Use and Health, which during Phase One repeatedly found that more than 75% of prescription drug abusers got their pills from friends, relatives, or dealers.[18] Of course, we are still left with roughly 25% who did have a prescription at one time, but that doesn't mean they all came by those prescriptions honestly.

Finally, in Phase Four when all hell breaks loose and toxic novel compounds are tearing through the population, this neatly packaged little theorem explaining the overdose crisis is revealed to be a reductio ad absurdam — meaning that when its initial proposition is taken to its logical conclusion, the result is so ridiculous that it disproves the whole premise that legal opioid prescribing for pain was the sole driver of the overdose crisis. (And it takes the magic molecule theory of addiction down with it.)

This blinkered telling of the Narrative of the Four Phases is a meta-scam that hides the many lesser scams beneath it.

This little theorem is destined to fail because it demands that we unsee the history that we and others have recorded. It packs the legacy heroin users and the Darlenes and the Lauras into one homogenous cohort. It discards the textured backdrop of illicit drug use and mortality that had been painstakingly reconstructed by researchers like Drs. Jalal, Burke, and Cicero. It even tries to obliterate the hard-won insights of dispassionate professionals like Commander Burke, Coleen Muse, and Dr. Schatman, who had been earnestly trying to dissect the disaster that was unfolding before their eyes.

At the end of the day, it is clear that this blinkered telling of the Narrative of the Four Phases is a meta-scam that hides the many lesser scams beneath it. It expects us to believe that every pill on the street went out the front door of a pharmacy on a facially valid prescription from a misguided or corrupt doctor, as if no one had ever lied to that doctor. As if no one had ever forged a prescription or rummaged through someone else’s medicine cabinet. As if no warehouses had ever been burglarized and no shipments had ever fallen off trucks. As if rogue internet pharmacies had not been allowed to thrive for years. As if such a lucrative black market for pills had somehow escaped the involvement of hardened criminal networks. Right.

One more thing: the magic molecule theory of addiction is itself a pushmi-pullyu. If you want to claim that glancing exposure to a pharmaceutical opioid carries a risk of addiction as high as, say, 25%[19], then you have to admit that the number of people currently afflicted by opioid use disorder should be far higher than it is. As bad as the overdose crisis has been — with deaths topping 100,000 in some recent years — it would have been almost unimaginably worse if the magic molecule theory were true.

Opioid medications were not invented in the mid-1990s. They had been essential to medical practice for decades when the pain movement began, primarily for acute pain. Think about all of the people still walking around who received an opioid prescription after major dental work, serious injury, or surgery. If one in four of them had been put at risk of lethal addiction with such routine exposure, then we would have seen apocalyptic levels of deaths. The COVID-19 pandemic would have looked like a walk in the park by comparison. Doctors would have corrected the trend and stopped prescribing opioids for anything long ago. Instead, the clinical use of opioids has persisted precisely because they are actually quite safe.

Part Four: The War on Prescription Drug Abuse

In 2011, when opioid prescribing had reached its peak and would soon plunge, a group called Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP) emerged as the voice of the federal government's campaign to end opioid prescribing for chronic, non-cancer pain. Its President, Andrew Kolodny, M.D.,[20] quickly became a media darling with his irresponsible rhetoric — calling pharmaceutical opioids "heroin pills," for example. Journalists are attracted to Dr. Kolodny because he reinforces the simplistic, two-sided, zero-sum, good-vs.-evil, melodramatic framing of the overdose crisis they already believe. This is precisely the kind of commentary Commander Burke warned us against in the clip I explained at the beginning of Part Two of this article.

In her conversation with Erica, Laura (from the gift shop) laments the fact that young people often don't realize how dangerous prescription opioids can be when abused. They don't know that they are an opium derivative, and opium is heroin, she says. By pointing this out to her friends, Laura is in effect trying to warn them off the path of drug addiction by putting the unsavory image of the heroin addict in their minds.[21] She is trying to protect them.

This is not what Dr. Kolodny is doing when he talks about "heroin pills." Dr. Kolodny is an experienced addiction psychiatrist, not a 20-year-old cashier in a gift shop. He surely should know that most of the deleterious effects of heroin use inhere in the fact that heroin use is illegal, not in the fact that street heroin — aka junk— is nominally an opioid. (In fact, pharmaceutical-grade heroin, diacetylmorphine or diamorphine, has been used safely in clinical settings to treat pain and addiction in other countries at other times.) By repeating the trope "heroin pills" ad nauseam, Dr. Kolodny is equating opioid prescribing for pain with drug dealing; and by extension, he is denigrating chronic pain patients who need opioid therapy as addicts. He is also maligning addiction patients — theoretically his own patients — by fanning the flames of addiction stigma with such talk.

Unlike Ms. Muse, Dr. Kolodny is not speaking the language of clinical compassion when he talks this way. He is applying traditional Drug War propaganda to a public health problem. Throughout our coverage in The PAIN GAME, we see Dr. Kolodny prefigured in other physicians occupying this same marginal space and spewing the same hysterical opioid nonsense that many politicians, prosecutors, and other officials use when they are in front of cameras. These figures are aggrandizing themselves as heroes in the War on Drugs while manipulating public fears around illicit drug use to demonize its victims. They are not trying to solve the problem. They are not trying to protect the public. Whether or not Dr. Kolodny and other physicians who engage in this kind of propaganda fully realize it, what they are doing is helping the DEA create a permission structure for cruelty.

The woman quoted above is Siobhan Reynolds, who started an organization called Pain Relief Network in 2003 to advocate for chronic pain patients and pain-treating doctors. She was one of the first members of the pain community to understand the political context in which they were being attacked. She was a fearless critic of the DEA. She died in a private plane crash at the end of 2011, shortly after PROP burst on the scene, announcing its grandiose mission in a press release called “The Goals and Claims of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP).”[22] I often wonder if PROP would have been able to overwhelm the media so quickly with their anti-opioid messaging if they had had to contend with Ms. Reynolds. We will see a great deal of her in The PAIN GAME.

Whether or not Dr. Kolodny and other physicians who engage in this kind of propaganda fully realize it, what they are doing is helping the DEA create a permission structure for cruelty.

Fast forward to July of 2021. The country is reeling from COVID-19 and Phase Four of the overdose crisis is raging. Yet, PROP chooses this moment to issue a press release flogging the tired mantra that opioids are ineffective for treating chronic pain, that they carry an unacceptable risk of addiction under any circumstances, and that it is opioid prescribing for pain that has been (and still is) powering the exploding overdose death rates from illicit novel compounds.[23]

To me, PROP’s press release reads as a frantic attempt to redirect public attention back to the reductive theorem of the Narrative of the Four Phases. It’s chilling. Think about it: if PROP could convince policy makers, the courts, and the public that there is no benefit in treating chronic pain with long-term opioid therapy — that there is only risk — then there would never be any instance in which opioid prescribing for chronic pain could be justified, and all of those patients we know are out there benefiting from such therapy could be disappeared.[24]

It was unlikely that PROP would truly convince many physicians that their absolutist view was correct. Physicians are trained in the art of balancing risk vs. benefit. They do it all the time, because there is always a balance to be considered with any medical treatment. But political considerations factor into physicians' calculations as well, unfortunately. Thanks to PROP's saturation of the media with its anti-opioid rhetoric, the political environment around opioid prescribing had become absolutely toxic by the end of Phase One of the overdose crisis. Thus, many prescribers grabbed onto PROP's message as if it were a lifesaver floating in polluted waters. They were glad to be relieved of the moral imperative to treat pain with opioids even when they believed it would be medically appropriate. PROP offered them a convenient rationalization for betraying their Hippocratic oaths and abandoning their patients.

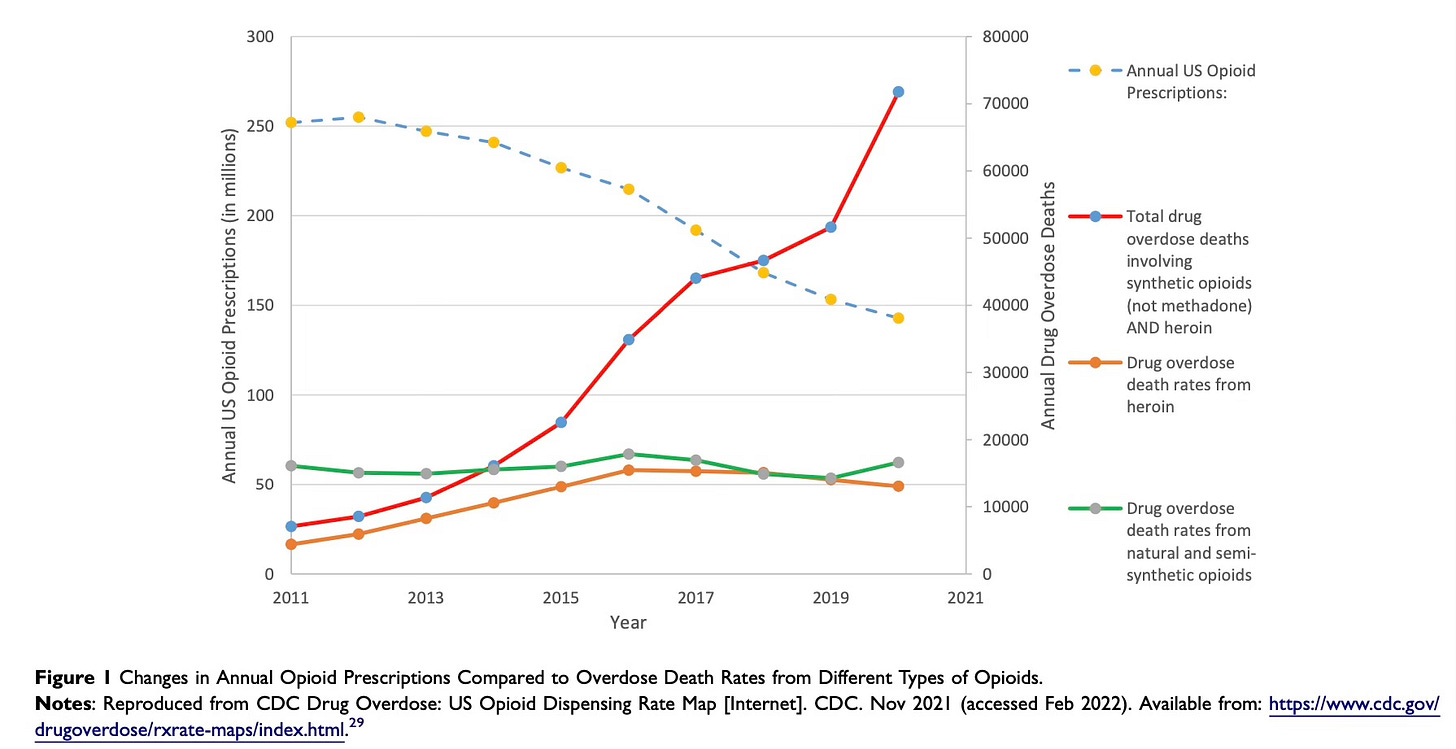

A few months after PROP's 2021 press release appeared, the CDC published this graph:

Picking up where the earlier CDC graph left off, here the green line of "Drug overdose death rates from natural and semi-synthetic opioids" is the continuation of what had been the blue line of Rx Opioid Deaths — and it's holding steady. Lines for heroin deaths (orange) and deaths from IMF and other novel compounds (red) have been added. We can see that the red line most closely follows the sweeping upward curve of composite overdose deaths that is the hallmark of the Jalal graph we examined in Part One of this article. This is what we would expected to see.

What is notable about this graph is the dotted blue-and-yellow line labeled "Annual US Opioid Prescriptions," which is the continuation of the green line of Opioid Sales from the first CDC graph. Right at 2012, shortly after the beginning of Phase Two, it abruptly turns and starts trending down. We see that the direct correlation between rising opioid sales and increasing prescription overdose deaths depicted in the first CDC graph has been completely disaggregated, and a striking inverse correlation has emerged between rapidly falling prescription opioid sales and skyrocketing deaths from IMF and other novel compounds.

No wonder PROP was trying to redirect public attention back to the reductive theorem of the Narrative of the Four Phases. In order to keep blaming doctors for the overdose crisis, we would have to affirm our faith in a super-charged version of the magic molecule theory of addiction: that mere exposure to an opioid exposes a person to an overwhelming risk of addiction, and that, given enough time, it is functionally inevitable that their addiction will result in fatal overdose. When we see how precipitously opioid prescribing has been dropping since the end of Phase One, and how dramatically this drop has coincided with an exponential rise in deaths from IMF and other novel compounds, it becomes quite a stretch to believe that most of the overdose deaths in Phase Four could be among patients who were prescribed opioids for pain years ago.

When the CDC published its first graph shortly after the close of Phase One of the overdose crisis, many people reasonably inferred that the "sharp increases in Rx opioid deaths" were the outcome of the "sharp increases in opioid prescribing" it depicted. Others dismissed the coincidence as an artifact and cautioned that correlation does not confer causation. Based on our detailed reporting of the events of Phase One, I take a more nuanced view.

I think the direct correlation between the rising green and blue lines staring us in the face when we look at that first graph is causative, but it is not linear. I don’t believe we can trace a one-to-one correspondence between patients who received opioid prescriptions in Phase One and the individuals whose deaths were reported as opioid involved during this period. The situation was much more complicated. In other words, I am confident that the rising prescription opioid deaths in Phase One cannot be reduced to coincident prescribing, or we would logically expect them to drop with declining opioid sales. Instead, the green line of prescription overdose death rates in the new CDC graph remains essentially unchanged from where it stood at the end of Phase One.

The space between the green and blue lines in the first CDC graph is filled, not just with diversion, but with many other twisted vectors of circuitous, paradoxical causation. It's a veritable corral of pushmi-pullyus. A graph cannot capture all of the naive expectations, misguided policies, system failures, subversive messages, and perverse incentives that converted opioid prescriptions into opioid deaths. For that, we must tell the actual story.

Beginning in the early 2000s, the DEA gradually began a campaign to cut off the supply of prescribed opioids altogether by decapitating the pain movement.

There was plenty of sloppy prescribing going on in Phase One of the overdose crisis, with too many patients getting modest but ill-conceived opioid prescriptions, and then not receiving adequate follow-up care or competent disease management. Such is the nature of our healthcare system. Even so, we can't look to casual prescribing by itself to explain why fatal opioid overdoses rose as much as they did.

Early in Phase One, there were kind-hearted actors like Commander Burke in state and local law enforcement — and even the DEA — who saw their mission as preventing pharmaceutical drug diversion while protecting access to pain care for legitimate patients. They were trained to fight crime, not to regulate the healthcare system; but they did their best to learn new methods and do no harm. Unfortunately, their nuanced approach would not win out over time.

Beginning in the early 2000s, the DEA gradually began a campaign to cut off the supply of prescribed opioids altogether by decapitating the pain movement. Rather than investigate sloppy prescribers, the DEA and federal prosecutors chose to target high prescribers; and in many widely publicized and very consequential cases, these high prescribers were the physicians who actually knew what they were doing. They were highly trained pain management specialists who drew the most intractable chronic pain patients from all over the country and committed themselves to caring for them thoughtfully. (A few of these prescribers were gifted internists who trained themselves in pain management.)

When these specialized practices were shut down, it was left to general practitioners to pick up their patients as best they could — knowing full well that they too would come under DEA scrutiny if their practices got weighted with too many pain patients. It was a mess. With too many doctors overwhelmed and too many patients left to their own devices, prescribing rose blindly, scammers had a field day, and fragile people perished with opioids in their system.

As early as 2005, it was clear that the situation was untenable.

If we wanted to create a visual representation of this regulatory dysfunction, we could do no better than the new CDC graph. It certainly looks like the downward trend in opioid prescribing is inversely contributing to the explosion of illicit opioid overdose deaths that is happening now. How could this be? By what mechanism could the reduction in the supply of pharmaceutical opioids — generally presented as a correction of over-prescribing — create such a disproportionate rise in fatal overdoses from illicit opioids?

In order to approach this unintuitive question, we need to understand the dynamics working on that line of falling blue dashes in the second CDC graph. Even in Phase One, when the green line of opioid sales was still rising, it was doing so despite relentless downward pressure exerted on prescribers that was present from the creation of the pain movement. It was not until the beginning of Phase Two, when PROP and other players piled on, that the DEA's campaign against opioid prescribing managed to bend the line down. Once it turned, it dropped steadily because the targeting of prominent pain management practitioners had chilled the whole healthcare system, and it emboldened law enforcement and other stakeholders to pursue more cynical aims under the guise of addressing the "opioid crisis." In other words, the turning of that slashing dotted line does not depict a gentle return to a more reasonable prescribing baseline. It was not a correction, but a brutal suppression.

The targeting of prominent pain management practitioners had chilled the whole healthcare system, and it emboldened law enforcement and other stakeholders to pursue more cynical aims under the guise of addressing the "opioid crisis."

The pain community was quick to identify the DEA's campaign against them as a new front in the War on Drugs, dubbed the War on Prescription Drug Abuse. They recognized it by the conflationary, denigrating language that was used to justify it — "Dr. Feelgood," "Schneider the Writer," "The Butcher of Pakistan," "drug dealers in white coats," rooting out "dirty doctors like the Taliban," and so on, and so on.

On a warm, windy day in the spring of 2004, Rev. Dr. Ronald V. Myers, Sr., organized a rally for pain patients and pain-treating doctors in Washington, D.C. Their hope was to pressure Congress to hold hearings and rein in the DEA's over-reaching campaign against opioid prescribing. One of the most powerful speeches given at the event was not by a patient or a physician, but by an attorney named Eric Sterling. Mr. Sterling, who founded and still directs an organization called the Criminal Justice Policy Foundation, had mastered the language of the Drug War when he served as Assistant Counsel to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary from 1979 to 1989. In that role, he was involved in the writing of increasingly draconian Drug War legislation. He also wrote speeches that members of Congress gave to justify that legislation. He was, in effect, a colonel in the War on Drugs, he says. Since then, he has been advocating to bring it to an end.

In his speech at the rally, Mr. Sterling places the pain crisis squarely in the context of the War on Drugs. He explains how decades of government propaganda has demonized a succession of vulnerable populations by coupling them with drug use in the public mind — Chinese-Americans and opium, Mexican-Americans and marijuana, African Americans and crack cocaine — even though study after study has shown that white Americans use illicit drugs at higher rates than any other group.

American drug policy isn't about protecting the American public from dangerous drugs, Mr. Sterling says. It isn't really about drugs at all. It is a sanctimonious rationalization for a stingy and cruel social policy that would deny healthcare, justice, and other forms of protection to those who need them most — immigrants, minorities, the poor, and the disabled. The OxyContin "epidemic" is another iteration of these successive racialized drug scares. In keeping with Mr. Sterling’s Drug War history, the OxyContin iteration can be seen as a pairing of white trash and “hillbilly heroin.” It is not an accident that has coincided with the perceived decline of white privilege among the poor.

Although the House Judiciary Committee on DEA Oversight did finally hold a hearing about the DEA's War on Prescription Drug Abuse on July 12, 2007[25], it was clear that Congress never had any intention of calling off the campaign and pulling the DEA out of the healthcare system. In fact, there would be many more Congressional hearings in which the DEA would be excoriated for not doing enough to bring down the supply of prescription opioids.

Like the Drug War overall, the War on Prescription Drug Abuse has failed spectacularly in its stated aim of protecting the public from dangerous drugs. It is perpetuated because it serves the unstated purpose of providing cover to Congress and a succession of Presidential administrations. The DEA’s brutal, eliminationist campaign against opioid prescribing provides the only narrative with which political leaders can appear to be addressing the overdose crisis without actually dismantling the interwoven hierarchy of scams feeding into it.

The DEA’s brutal, eliminationist campaign against opioid prescribing provides the only narrative with which political leaders can appear to be addressing the overdose crisis without actually dismantling the interwoven hierarchy of scams feeding into it.

In the reign of terror that the DEA has created, most doctors have stopped prescribing opioids completely. Others are tapering patients down, against the patient's will in some cases — even compliant, stable, long-term chronic pain patients with well-established diagnoses, like Darlene. Other entities have jumped on the bandwagon with their own opioid "sparing" efforts. State legislatures have mandated pill limits for acute pain. The State of California combed through old death certificates to find opioid overdoses that could be pinned on prescribers years after the fact. Insurance companies are sending insulting warning letters to doctors and refusing to fill prescriptions even for tramadol, an opioid that is so weak it wasn't even considered a controlled substance until 2014. Prosecutors are mining prescription drug monitoring programs and other databases for prescribing "outliers" — which at this point is just about anyone willing to prescribe opioids for pain at all. Surgical groups are vying for grants to develop opioid-free post-operative protocols for even the most difficult surgeries. Emergency room physicians are throwing anything but opioids at trauma patients. Even cancer and end-of-life patients are now being denied pain relief. It's a giant pig pile crushing pain patients beneath it.

The overdose data that Jalal et al. gathered for their famous graph begin in 1979, because that is when the coding of such deaths was standardized in a way that made it possible to analyze them consistently going forward. It's not difficult to imagine the line of composite deaths in the Jalal graph extending back a little bit to 1973, when the DEA was created to fight the modern War on Drugs, or even to 1970, when the Controlled Substances Act was enacted to replace the Harrison's Narcotics Tax Act of 1914. The point is that the sweeping upward curve of overdose deaths in the Jalal graph is a powerful indictment of the modern War on Drugs. Could it be that the War on Drugs has actually made America's drug problem worse? The answer is yes.

Drug prohibition and control — or more precisely, the cynical politics underpinning it — has contributed to the demand for drugs in this country. The problem isn't just that the War on Drugs has been unsuccessful in keeping illicit drugs off our streets — it is that it has been unsuccessful for so long. It is a political misadventure that should have been corrected years ago when participants like Eric Sterling correctly assessed the damage it was doing to our entire culture.

Drug prohibition and control — or more precisely, the cynical politics underpinning it — has contributed to the demand for drugs in this country.

Instead, the modern Drug War has been propagated for half a century, during which its intended and unintended effects have been locked in by commercial and criminal interests. It has become normalized as the ecosystem within which many of our institutions operate — certainly the criminal justice and prison systems, but arguably also the financial system, foreign policy, domestic programs, and — as The PAIN GAME reveals — even the healthcare system.

The War on Drugs is a scam that has been foisted on the American people with breathtaking cruelty, and Americans are opting out. The mechanism by which drug policy is converted into drug deaths is political trauma. When people are treated badly enough for a long enough time — especially by such a powerful, paternal sovereign entity as the federal government — eventually many of them will internalize the abuse and self-deport from life.

Notes:

1. Pert & Snyder, The Opiate Receptor: Demonstration in Nervous Tissue. Science 1973 Mar 9;179(4077):1011-4.

2. Snyder, Brainstorming: The Science and Politics of Opiate Research; Harvard University Press, 1989; p 133.

3. See Melzack & Wall, The Challenge of Pain, updated second edition; Penguin Books, 1982.

4. Clinical Instructor, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative Care, and Pain Medicine, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York City.

5. See Schatman ME. The role of the health insurance industry in perpetuating suboptimal pain management. Pain Medicine 2011; 12:415-426.

6. Schatman ME and Webster LR. The health insurance industry: perpetuating the opioid crisis through policies of cost-containment and profitability. Journal of Pain Research 2015; 8:153-158.

7. Jalal, et al. Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016. Science 361; 1218 (2018).

8. 21 U.S.C. § 1504 (1988).

9. NADDI presentation filmed for The PAIN GAME; November 16, 2004; 123A_NADDI_Bizzell_Muse: abandoned pain patients.

10. Courtwright, Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America; Harvard University press, 1982, revised edition 2001; p180.

11. Professor Emeritus of Neuropharmacology, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

12. Cicero, et al., The Changing Face of Heroin Use in the United States: A Retrospective Analysis of the Past 50 Years. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71(7):821-826.

13. Cicero, Ellis & Kasper, Increased use of heroin as an initiating opioid of abuse. Addictive Behaviors 2017; (7):463-66.

14. PAIN GAME interview, November 20, 2004; 135_NADDI_gift_shop girl: I've been hooked on prescription drugs.

15. Noble, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD006605.

16. Cicero, et al., The Changing Face of Heroin Use in the United States: A Retrospective Analysis of the Past 50 Years. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71(7):821-826.

17. Carise, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 November; 164(11): 1750–1756.

Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. SAMSHA Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. As cited in Singer JA, Sullum JZ, and Schatman ME, Today's nonmedical opioid users are not yesterday’s patients; implications of data indicating stable rates of nonmedical use and pain reliever use disorder. Journal of Pain Research 2019:12 617-620.

Studies give results ranging from <1% to >25% because there is no consensus on how to define opioid addiction among pain patients. The 25% number is what has been cited by Dr. Anna Lembke, an addiction psychiatrist at Stanford University, while serving as an expert witness in various opioid litigation trials — not always successfully.

Senior Scientist, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts.

PAIN GAME interview, November 20, 2004; 135_NADDI_gift_shop girl: people don't realize they're taking heroin.

PROP News Release: The Goals and Claims of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP); September 15, 2011.

PROP News Release: Prescription opioids continue to contribute to the rise in drug overdose deaths. July 21, 2021.

For a thorough rebuttal of the PROP press release see Bettinger, et al. (Schatman); Journal of Pain Research 2022: 15 949-958.

Siobhan Reynolds, a prominent patient advocate and founder of Pain Relief Network, testified before the Committee. Reynolds_Congressional_testimony_07.12.07.

The PAIN GAME videos, in order of appearance:

NADDI_conference_Burke_4: two sides to every story.

NADDI_conference_Burke_4: two sides to every story. [longer version]

144_Darlene_redigitized: they didn’t care; 144_Darlene_redigitized: finding it on the streets.

NADDI_conference_Burke_2: every doc gets scammed.

012_McCune_redigitized: there’s nothing wrong with the drug.

Passik_Webster_interview_CamB_HR: 90% of us have been exposed to opioids; Passik_Webster_interview_CamB_HR: addiction is not inherent in the drug.

Siobhan_Screening_04_15_05_51: the_brutal_effect_of_downward_pressure.

Fisher_Interview_04_03_05_09_01: dysregulation.

The PAIN GAME video: 007_04_18_04_redigitized: Drug War is a secular crusade; 007_04_18_04_redigitized: OxyContin is the latest manufactured drug scare.

015_Myers_redigitized: where we’re headed as a nation; 015_Myers_redigitized: you could be next.

© 2025 Quarter Turn Media LLC

Readers who are intrigued by this argument will find many of the same arguments — with many of the same sources — in my book, Your Body, Your Health Care, published by the Cato Institute in April 2025. https://www.cato.org/books/body-health-care