Right Too Soon

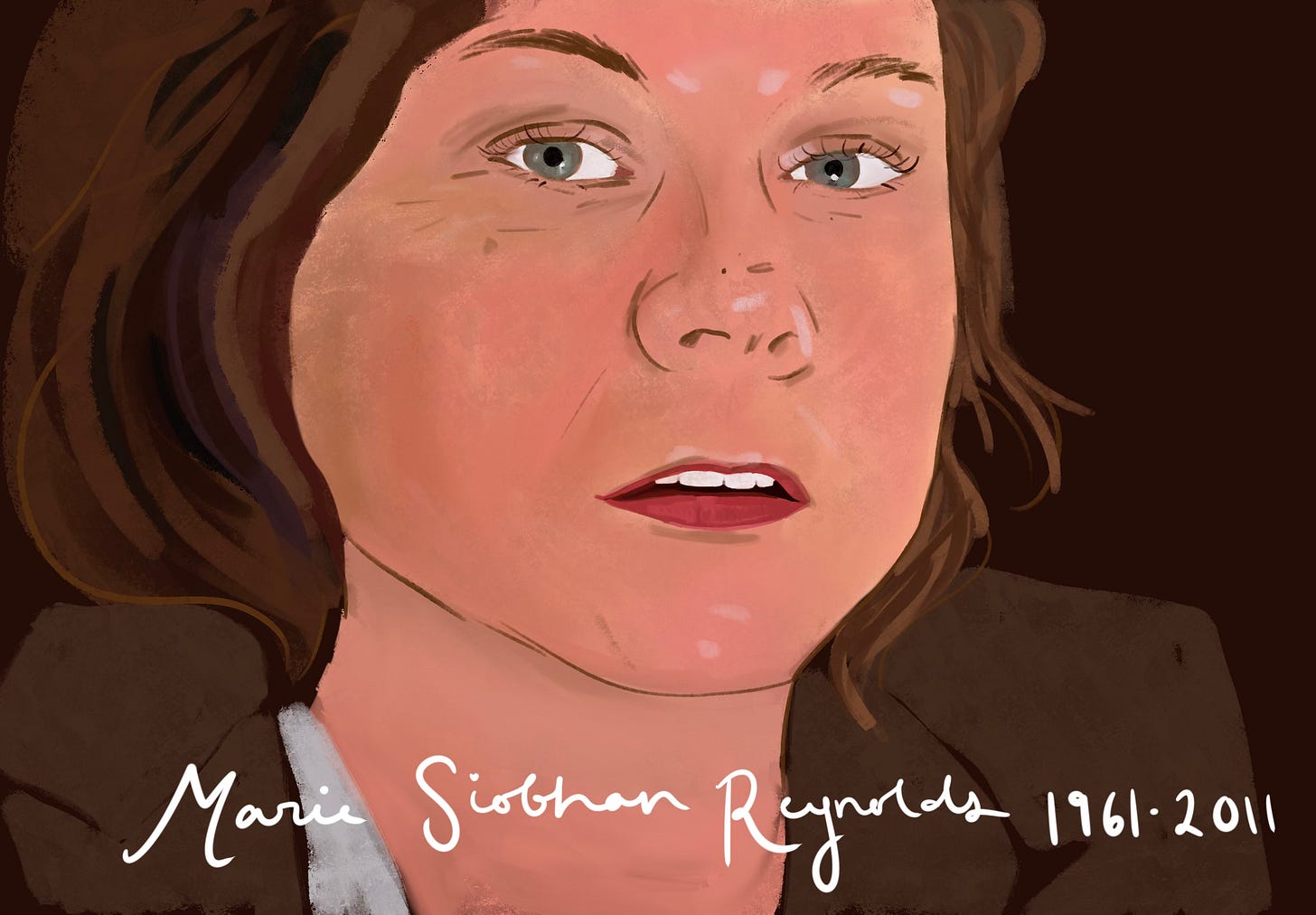

The Legacy of Siobhan Reynolds

[Disclaimer: I have recounted some dramatic events in this piece from memory. I was unable to document them at the time, or the documentation has disappeared. They were my direct experience, except for one incident (the dog on the wall) that was reported to me immediately after it occurred by two people who I believe were telling me the truth — Siobhan and her son.]

Quarter Turn Media launched The PAIN GAME at the end of March into the worst media environment in a generation. Not since the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks has news and commentary been so mono-thematic: all Trump, all the time. This coverage is necessary, of course, and much of it is perceptive; but there seems to be no oxygen for a story that isn't obviously, directly related to the rapacious political vortex that is the second Trump administration.

The timing for The PAIN GAME has always been difficult. There were several turns along our path where Erica and I paused and wondered if we should even bother to go on. For more than 20 years, we have persisted in filming, researching, and writing this project against a blistering political headwind. It is deeply exhausting to have been immersed for so long in a story that is so dramatic, so morally demanding, and so uniquely revelatory of our country's political decline — yet, so difficult to present.

At first I thought we were up against the old publishing conundrum that book editors (including myself) confront when rejecting manuscripts that seem compelling but probably don't have legs: If this issue is so prevalent and so important, why have I not heard about it before? Eventually I realized that we were facing something more impenetrable: Americans just didn't want to believe that the federal government — their government — is as disingenuous, as corrupt, and as thuggish as it is. Whenever we tried to explain the gist of our project to people, we could see our interlocutors frantically constructing a barrier around their minds to keep our message out. We called this barrier the cognitive wall.

What makes our story so difficult to comprehend is both its innate complexity and the disturbing cynicism it exposes. It is difficult for Americans to understand how and why the U.S. Department of Justice would criminally prosecute innocent people for veiled political reasons. Our defendants are medical professionals who were prescribing or dispensing opioids for pain in a manner that is legal, as well as medically appropriate. They were targeted as part of a decades-long campaign by the federal government to achieve three covert ends: 1) to deny healthcare to disabled people; 2) to claw back a designated percentage of money paid out annually by Medicare and Medicaid; and 3) to allow political leaders to say they are addressing the opioid crisis.

Americans just didn't want to believe that the federal government — their government — is as disingenuous, as corrupt, and as thuggish as it is.

I keep thinking about this passage from Sarah Kendzior's book, They Knew:

It is very bad in America to be right too early. It is considered a sin in journalism to tell the public what you have learned in real time, both because you are going against the tide of profit motive, but mostly because it destroys plausible deniability for the corrupt and powerful. My dire warnings were echoed by political officials only when it was too late for them to act.[1]

Ms. Kendzior is talking here about her own reporting leading up to Donald Trump's first election to the U.S. Presidency in 2016, and how she felt like a lone voice in the wilderness documenting his unfitness for office, and foreshadowing the disaster that awaited this country if he were to be elected.

This is a disturbing description of the cognitive wall. The message here is not that the public might not be ready to hear what you have to say; it is that the corrupt and powerful may keep you from saying it. This is what happened to Siobhan Reynolds, who was trying to warn the country about a different issue at a different time. It was through Siobhan that I was ushered into the pain world and learned about the DOJ's brutal campaign against opioid prescribing for pain.

The message here is not that the public might not be ready to hear what you have to say; it is that the corrupt and powerful may keep you from saying it.

The dark decade during which Siobhan and I worked together began and ended with unspeakable tragedies: the September 11 attacks in 2001, and her violent death at the end of 2011. Siobhan was living in New York City at the time of the terrorist attacks, and I was commuting in every workday from Westchester County. About three days after the terrible event, the television news coverage of it shifted abruptly from gritty, looping videos of people jumping from the upper storeys of the towers to heartwarming vignettes of the heroic firefighters who had run into the collapsing buildings. The firefighters were indeed courageous, but it was disorienting to be presented with comforting, commemorative material when the stench of the smoldering remains of the towers still hung in the air. This was not the information or analysis New Yorkers needed in the immediate aftermath of such an existential catastrophe. It felt like something was being withheld.

It was clear that someone had lowered a censorship boom on all of the U.S.-based television stations, and it could only have been the federal government. My partner and I switched to watching the BBC (only when his young daughter was not present, as their coverage was indeed graphic). I had worked in media since I was 15. I knew how it could be manipulated. Indeed, in my corner of the industry, I had become adept at manipulating it myself to promote the sales of particular books. I had never before considered that the government had such a strong hand in controlling the news in this country, however. I started to look askance even at the New York Times, although I continued to read it daily for a long time. I turned hungrily to the New York Review of Books, which I still read faithfully.

Siobhan asked me to help her write a book about her work advocating for pain care and supporting physicians who had been wrongly convicted of illegal opioid prescribing. She was an activist, not a journalist. Hyperbole was her stock in trade. We argued constantly about the tone she adopted on the page. I urged her to describe only what she had witnessed firsthand and limit her commentary to the insights she had gleaned from her experience. That would be a hard enough sell, given how truly bizarre her journey had been. I would lose this battle with her, however, and her book would never be published. But in the process, I came to appreciate how extraordinarily perceptive she actually was. I realize now that her timing may have been more of an issue than her tone. She was right, but she was right too soon.

Siobhan understood political power much better than I did. Her mother came from an old-money family in Chicago. Her father's family was related to the Kennedys by marriage, twice. Siobhan initially devoted herself to the cause of helping chronic pain patients in order to help her husband, Sean, who suffered from a connective tissue disorder that went undiagnosed for years. She continued her advocacy after Sean's death out of a sense of political noblesse oblige. I didn't fully understand this until now (when it is already cliche), but one of her great insights was that what defines class in this country is not wealth or occupation — and it obviously isn't virtue or ability. It is proximity to power. Siobhan felt obligated to help pain patients because she was closer to power than they were. Pain patients tend to be poor, disabled, and invisible. They are some of the most vulnerable people in our society.

You might think that doctors would be harder targets with their education, comparative wealth, and local social standing. But those things can't help you much when a federal criminal indictment blindsides you. What you need then is to be able to pick up the phone and call someone who is closer to power than you are, especially if that person can, in turn, call someone in Washington.

Siobhan felt obligated to help pain patients because she was closer to power than they were.

Siobhan founded an organization called Pain Relief Network (PRN) in 2003. When she got a call from a physician who had been indicted, she would first ensure that she believed the indictment was unjust. Then she would connect the physician with attorneys who had experience defending against such prosecutions. She would also put the defendant in touch with other doctors who had been through the same ordeal. PRN really was a network. The defendants usually were completely bewildered by what was happening to them, because they hadn't actually done anything illegal. It was important for them to know that there was a little world of healthcare professionals who had been unfairly targeted, and that the action against them was part of an orchestrated campaign the DOJ was waging against opioid prescribing all over the country. It was political, not medical.

Siobhan's most important role was dealing with the media. She would always find that local reporters were already dependent upon the prosecutor for information by the time she got to the scene. With a bit of coaching, she usually was able to get a few of them to do some original reporting and present the case as something bigger than a local crime story. She would organize press conferences for the patients so they could show their communities that they were not just a bunch of drug addicts. She achieved some personal renown after handling about 30 such cases over the years, but she could never overcome the dominant narrative of the opioid crisis: all OxyContin, all the time, opioids all bad. Like the cognitive wall, this narrative was fixed in place.

Siobhan made the classic rookie mistake of believing that she just needed to get the ear of someone in Congress and reveal what was happening — that the DOJ and DEA were knowingly destroying people in pain. That person would then feel a responsibility to address the issue, or at least they would no longer be able to claim any plausible deniability to justify their inaction. Siobhan testified before a Congressional committee, but she made little impression. She tried to host a screening for Senate staffers of the documentary she had made, The Chilling Effect; but no one showed up. She held a press conference at the National Press Club, but it was sparsely attended. She learned the hard way that Washington is where pressing issues go to die. She slammed up against the same appalling truth that had brought Sarah Kendzior up short: the people in Washington who could have stopped all this — the people in the inner sanctum of power — already knew. They knew long before Siobhan did; they had their own reasons for letting the brutality continue.

Siobhan learned the hard way that Washington is where pressing issues go to die.

It was in 2005, halfway through our dark decade together, that Siobhan fully took in the moral import of this implacable reality. Here she is in a hotel room the night before Dr. William Hurwitz was convicted for the first time. Dr. Hurwitz is a well-regarded pain management specialist, and his trial attracted the attention of the whole pain community. (He was also treating Sean at the time, quite successfully.) Many patients and defendants came to the federal courthouse in Alexandria, Virginia, to show their support for him.

In this clip, Siobhan is talking to Steve and Madeline Miller, pharmacy owners who had been defendants alongside Dr. Frank Fisher in California in the 1990s.

It was around this time that Siobhan moved back to Santa Fe, New Mexico, with Sean and their teenage son. Sean was close to death, and their son was medically and emotionally fragile. (He had inherited his father's connective tissue disorder.) We all had roots in Santa Fe. Sean and I had been classmates at St. John's College, and it was through him that I met Siobhan. Siobhan had gone to graduate school at the College. She moved her family into her mother's house, and soon they were under surveillance.

Siobhan was fearless and wickedly funny. I learned a great deal watching how she engaged the federal government in an ongoing and dangerous, yet delicate dance. She called it a pavane, which is a 16th-century court dance in which couples advance and retreat in carefully choreographed steps. (I don't know where she got this word. I had to look it up. Wikipedia calls it a "decorous sweep.")

One time when I was visiting Santa Fe, we left our phones in the house and took Siobhan's dog Julia for a long walk. She told me that she was sure someone was listening to her calls, and she wanted to try an experiment. She was going to introduce false information into our telephone conversations to see where it went. We knew each other well enough by then that I had no trouble detecting what was false, and I went along with the scheme. Sure enough, random factoids from our conversations would show up in the local media in Kansas, where she was working on a case, and in the columns of an anti-opioid blogger who was close to the prosecutor there. We even saw them pop up in court filings, because the prosecutor was in the habit of sprinkling legally meaningless yet vaguely defamatory content throughout her motions to the Court. The surveillance became a two-way channel when Siobhan started introducing disinformation that would trip up the prosecution strategy. Her gambit was characteristically brilliant and reckless.

The surveillance became a two-way channel when Siobhan started introducing disinformation that would trip up the prosecution strategy.

There were many times when we would be sitting in a restaurant and Siobhan would say something to me like, "Don't look now, but check out that guy by the door." I would wait a moment and then look. Sure enough, there would be a beefy man sitting there alone, staring at us and trying to look menacing with his arms crossed and his legs spread apart. Sure enough, Siobhan would go right up and engage him in conversation. I couldn't always hear what they were saying, but I could tell by their body language that she was disarming him with charm. He would uncross his arms and smile in spite of himself. He would look sheepish. Sometimes he would even blush a little. Then he would leave.

We talked on the phone almost every day when I was back in New York. It was obvious that someone was indeed listening to our calls, because we would lose our connection at predictable moments. We were using iPhones by this time. It wasn't like in old movies when you can hear clicks on a landline. We had to test our hunch. We painted a verbal picture of a poor grunt in a cubicle at some National Security Agency office assigned to suffer through hours of our girl talk. We speculated that he was young and pale, and that he lived in his mother's basement and never got laid. Siobhan would make up lewd stories to embarrass him. Sure enough, he’d drop the call when we talked this way. He would also drop the call when we brought up anything strategic. Sometimes we had difficulty making plans. It became clear to us that the purpose of this eavesdropping was not only to gather information, but also to intimidate us and disrupt our work.

After enduring a year or so of surveillance, Siobhan started getting threats by email almost daily. She showed them to me, and then forwarded them to someone else to be archived. (I'm told this archive has been lost.) She could never figure out where the emails were coming from. Whoever was writing them was careful never to threaten her life. The message was always that they — whoever "they" were — would burn down her house and kill her dog.

The message was always that they — whoever "they" were — would burn down her house and kill her dog.

Sean had passed on by this time, and Siobhan and her son had moved out of her mother's house and into an apartment. She told me that one day when she was returning home from doing errands, she was approaching her door through the back garden when she was confronted with a horrifying sight: the dog from next door was hanging, dead, over the adobe wall by his leash and collar. It was a high wall; there was no way this dog could have gotten over it on his own. Julia was safe inside the apartment.

Siobhan brought Julia to live with my family and me in Westchester County after that. One day, I was walking Julia in our neighborhood when an unmarked van pulled up alongside us. The side door slid open, and I could see a man's legs and feet. He was trying to get ahold of Julia without getting out of the van. I don't remember if I saw his face; I was watching his hands. Julia was a big and clever dog — part German Shepherd and part red wolf — and she was able to elude his grasp. We hurried down a side street that led to a footpath and a high staircase descending a bluff to the commuter rail station below. I figured that by the time the van got around to the bottom, Julia and I would be close to home. We were already on our block when it caught up to us. We zig-zagged through a few backyards and got safely into the back door of our house. Sitting on the living room floor with my arms around Julia — both of us breathing hard — I knew the pavane was over, and the hunt was on.

Sitting on the living room floor with my arms around Julia — both of us breathing hard — I knew the pavane was over, and the hunt was on.

I suspect that if Siobhan had lived longer, she would have embraced Donald Trump's MAGA movement. Her struggle with the DOJ had definitely moved her to the right. She wanted to document her political evolution in her book. She had been sending me little voice notes of ideas so I could incorporate them into the manuscript. In one recording, she described how she had gone from a staunch liberal Democrat to a classical liberal, or libertarian — but she really was a Constitutionalist[2]. This did not surprise me. The investigative abuse and prosecutorial misconduct in these prescribing cases were so egregious that many of us who witnessed them turned for solace to the U.S. Constitution, chapter and verse. Siobhan was picking up on something much bigger, however. She was anticipating a political inversion that would soon convulse the entire country.

Siobhan was not alone in thinking that the federal government had grown so intrusive that it threatened Americans' personal liberty. She was drawn to the Tea Party Movement and all its cosplay. She talked about buying a tri-corner hat. She already owned a handgun. The handgun was probably a necessity, given her situation; but I was skeptical of the Tea Party's cultural conflations. I told her it was a fallacy to try to impose an ideological solution on a historical problem. She just laughed. I had an uneasy feeling that she was running directly at what fascinated her, even though she recognized it as dangerous. Like a kid who keeps getting back on the scariest ride at the carnival, she remained astride a seditious political current because the sheer motion of it was exhilarating. She was seeking anarchy, not reform.

In the last year of her life, it seemed to me that Siobhan was no longer evolving, but was becoming radicalized. She spent a great deal of time on Facebook, where she positioned herself as a pundit on all things political. I warned her that she was undermining her credibility, giving her detractors all the more reason to dismiss everything she had ever said. Professional expertise still mattered in those days, and no substantive person in politics or media wanted to hear quasi-legal commentary from someone who had dropped out of law school. I lost this battle as well. She was too traumatized to care anymore. She was never going to have her moment, or so I thought.

Like a kid who keeps getting back on the scariest ride at the carnival, she sitting astride a seditious political current because the sheer motion of it was exhilarating.

In 2009, Siobhan became the target of a federal grand jury investigation. She never knew what her alleged crime was. Grand jury matters by law are shrouded in secrecy. Siobhan's attorney was told it had something to do with obstruction of justice, a charge that is so vague and overused it is practically meaningless. The grand jury had been convened at the behest of the prosecutor in the Kansas case. She was seeking all of Siobhan's correspondence related to that case, which had not yet gone to trial. It was an obvious gambit to expose the defense strategy.

Siobhan resisted complying with the subpoena seeking her records for as long as she could in order to protect the Kansas defendants. She was held in contempt of court and levied with daily fines until she was broke. She and her son were rendered homeless. They wandered the country, staying with various friends. She was threatened with incarceration, which terrified her. (Typical Siobhan: she died wearing a Bureau of Prisons jacket I had given her as a joke.) I could see whenever she came to me in New York that the strain of it all was breaking her. She was completely, absolutely vulnerable. She had nowhere left to go but in the ground.

Sure enough, Siobhan died in a private plane crash along with her romantic partner, Kevin Byers, who had been one of the defense attorneys in the Kansas case. It was the morning of Christmas Eve, 2011. Kevin liked to fly as a hobby. They had taken his little plane to go and pick up his mother for the holiday. The last email I got from her was a recipe.

In the summer of 2010, Siobhan had told Erica in an interview that she was trying to get the U.S. Supreme Court to take up her grand jury case. It was the final step available to her, and she wasn't optimistic. The ACLU had represented her in the lower court and then dropped her case; and the Tenth Circuit had denied her appeal. Now two prominent attorneys in Washington, Jeffrey Parker[3] and Robert Corn-Revere[4], were preparing a writ of certiorari asking the high court to hear her case as an important First Amendment matter. Since her attorneys couldn't see the actual charge against her, they argued that the abusive nature of the grand jury subpoena was evidenced by the events leading up to it. They tallied the progression of increasingly harsh actions the Kansas prosecutor had taken to try to silence Siobhan. They claimed that Siobhan had been targeted for her speech and association (via PRN) — in other words, for her activism.

The case was both crushing and inscrutable. The Supreme Court declined to hear it.

Doesn't any of this stuff matter? To anybody?

This is the question Siobhan left hanging in the air when she crashed to the ground.

When Donald Trump rode down his golden escalator in 2015 and announced he was running for President, he took the cognitive wall down with him in one indecorous, fell swoop. Like Ms. Kendzior, I was less surprised by this than many other people were. Too many lies had piled up behind the cognitive wall. Too many truths had been withheld. Too many problems had gone unaddressed. Too many scandals had come and gone with no one in power held accountable. Americans had been asked to accept too many political fictions, as Joan Didion called it way back in 2001, in a book that arrived in stores on the very day the towers fell[5]. The cognitive wall was a dam destined to break.

People can't look directly at naked power any more than they can look into the sun. Trump held a trick mirror up to the federal government and invited his voters to mock it. When he talked about "fake news," "witch hunts," and “the deep state," he was twisting these terms away from what they really signify to distract the country from his own criminality. It was easy. Americans no longer cared about criminality. Even people like Siobhan had been made into criminals. Like so many malignant things in our society, criminality had become a joke; and Trump's genius was to make voters out in the country far from Washington feel like they were finally in on it.

People can't look directly at naked power any more than they can look into the sun.

Siobhan's final question hung in the air until Trump stole the words we would need to answer it. Most of the media accounts that claim to explain the origins of the opioid crisis reduce it to the over-marketing of OxyContin. Like the post-9/11 coverage I described, this really is fake news. I've written before about what it conceals. Many times in The PAIN GAME we hear defendants, attorneys, and even random observers characterize the physician prosecutions we have covered as witch hunts, because that is what they are. And there really is a deep state. It is not comprised of ordinary federal employees, as Trump says. It is the mysterious "they" that threatened Siobhan. I suspect that during Siobhan's time it was a small minority of federal employees, a little cabal of power-tripping agents and officials lurking somewhere inside the federal bureaucracy. During the dark decade I spent with Siobhan, and in the years since her death while Erica and I continued reporting on The PAIN GAME, it seemed that this cabal grew larger and more dominant. I worry that with the mass purging of the federal workforce that the second Trump administration is pursuing the deep state will become stronger. The cabal will be in the majority.

The subtitle of Ms. Kendzior's book is How a Culture of Conspiracy Keeps America Complacent. I don't know if it was a conspiracy that put Trump in office. It's possible. What I see is a mostly hidden yet durable thread of abuse of power that runs through Siobhan's time to the present day. Ultimately, Siobhan's most important contribution was forcing the federal government to reveal its dark face by provoking its brutal tactics. Her greatest strength was her vulnerability.

With the publication of The PAIN GAME we will salvage the appropriate words from Trump's rhetorical rubble, and delineate the steps of the pavane. It is a distinctive pattern we need to study, a playbook still in use. Trump didn't come out of nowhere. The reason he has been able to be so destructive so quickly is because he was handed an effective, unaccountable federal apparatus with the cruelty already built into it.

Siobhan's most important contribution was forcing the federal government to reveal its dark face by provoking its brutal tactics.

The PAIN GAME is a work of journalism, not activism. It is an investigative history that captures the activity of many characters. It is not the continuation of Siobhan's book. Still, it is Siobhan's tragic personal trajectory that gives The PAIN GAME its direction, and her prescient insights that foreshadow its destination as a penetrating critique of American power. It's astonishing, actually, how precisely the events we've filmed prefigure our current political moment, thanks to Siobhan’s sacrifice. This is her moment.

So, The PAIN GAME is about Trump after all. I'm glad we're launching it now, and I'm glad we’re doing so on Substack. I can see how we fit into a community of reporters and commentators who are earnestly trying to figure out how America got here, and how we can move on. It gives me hope.

Notes:

They Knew: How a Culture of Conspiracy Keeps America Complacent; Flatiron Books, ebooks, 2022; pp 8-9.

The PAIN GAME, Reynolds voice note; The change: a real American.

Professor Emeritus of Law, Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University.

At the time, Mr. Corn-Revere was a partner at Davis Wright Tremaine. In 2023, he joined the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) as Chief Counsel.

Didion, Political Fictions: Vintage Books, 2001.

The PAIN GAME video/audio clips, in order of appearance:

The PAIN GAME video; Hurwitz_Trial_Siobhan_the_Millers_in_Hotel_room_preverdict_0: everybody’s protecting themselves.

The PAIN GAME, Reynolds voice note; In Liberal: swinging against itself.

The PAIN GAME interview; Schneider_verdict_Siobhan_Kevin_2: doesn't any of this matter?, 2010.

The PAIN GAME, Reynolds voice note; Assume Stupid: if it is a conspiracy.

© 2025 Quarter Turn Media LLC